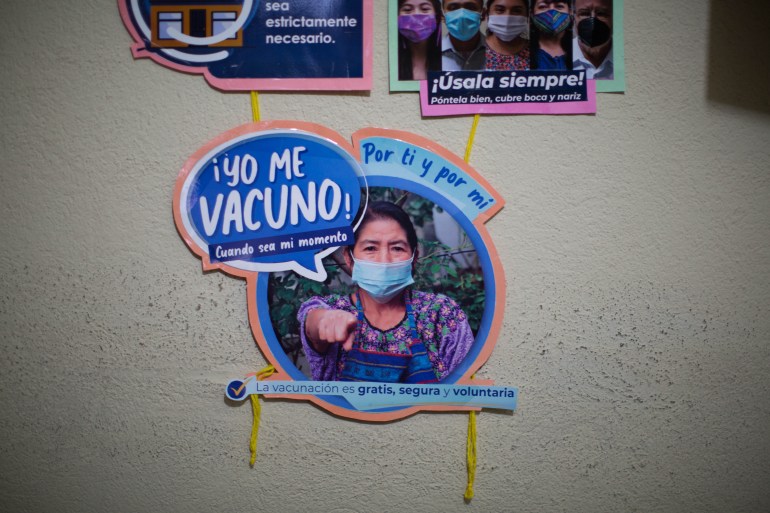

Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala – On a recent afternoon, the COVID-19 vaccination centre in the heart of the Indigenous Mayan town of Santiago Atitlan was quiet. The health centre had a vaccine supply, but demand was low.

The lack of coordination of a Guatemalan government-led campaign to overcome vaccine hesitancy has resulted in the expiration of millions of doses across the country this year, critics have said, as more than half of the population remains unvaccinated.

According to Juan Manuel Ramirez, an evangelical preacher in Santiago Atitlan, some community members have taken the vaccine, knowing it helps to protect against severe disease. But others have subscribed to conspiracy theories about its potential dangers.

“There are other people who also have other types of thoughts, such as that the vaccine comes with a chip,” he told Al Jazeera. “Because of that, there is uncertainty, and therefore they have not been vaccinated.

Earlier this month, approximately 1.5 million doses of the Moderna vaccine donated by the United States expired. In March, the same fate befell nearly three million doses of the Russian-made Sputnik V vaccine, worth more than $33m. And by the end of June, more than two million doses of the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines will also expire.

“The main factor of the expiration of the vaccine is a very slow rate of vaccination,” Oscar Chavez, cofounder of the GT Data Laboratory think-tank, told Al Jazeera. “The vaccination rhythm is very inefficient.”

Problems with access

Guatemala has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the Americas, with about 48 percent of the population receiving at least one dose and fewer than 20 percent receiving three doses, according to health ministry data. The Guatemalan government has cited the resistance of the population to its vaccination campaigns as the reason for the mass expiry of doses.

“We have tried to make available all the vaccines of different brands to the public,” Guatemalan Health Minister Francisco Coma said in a media statement. “Unfortunately, there has been a rejection among the public to vaccination.”

But experts have contended that the larger problem is the Guatemalan government’s failure to facilitate access to the vaccine for marginalised groups or to combat the spread of misinformation.

“It isn’t that the people do not want to be vaccinated; rather, it is a problem of access,” Chavez said. “The government has not facilitated access to the vaccine to everyone.”

Guatemala’s vaccine rollout was chaotic from the outset, as the country was late in obtaining doses and relied largely on donations. The government also faced criticism for failing to develop an adequate vaccination strategy, particularly in rural areas that lack internet access and mobile phone coverage. All of which eroded public trust.

Compounding matters, alleged anomalies in the government’s $160m deal to buy millions of doses of the Sputnik V vaccine spurred an investigation by the country’s anti-corruption prosecutor’s office.

“What I see is a lack of planning and foresight,” Nancy Sandoval, an infectious diseases specialist and former president of the Guatemalan Association of Infectious Diseases, told Al Jazeera. “This had an impact on the perception and trust of vaccines.”

Many communities did not have the necessary infrastructure to administer the vaccines, setting off protests from medical workers. In other areas, residents said they were not provided with timely information about the vaccines in their Indigenous languages.

While a spokesperson for the Guatemalan presidency told Al Jazeera that the government ran campaigns specifically targeting Indigenous communities, critics say these efforts failed to adequately combat vaccine misinformation.

Conspiracy theories

Santiago Atitlan was one of the communities where conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 vaccine gained a foothold. One local evangelical church became a breeding ground for such misinformation, as churchgoers regularly participated in mask-free marches through the town.

“Unfortunately, people believe lies more than truth,” Ramirez said. “Since there has been fear, then people refuse to get vaccinated.”

Al Jazeera approached more than a dozen people in Santiago Atitlan, but all declined to comment publicly about their views on the vaccine.

Meanwhile, Ramirez has taken steps to preach the benefits of the vaccine to his congregation of around 400 people. Municipal authorities have also sent health workers door-to-door to promote the vaccine, but even with these efforts, many residents have remained resistant.

One health worker, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, told Al Jazeera that they were not getting enough support from the health ministry, and that individual health providers could be charged for any vaccines that expired.

The government’s failure to address such concerns and to build trust within communities has been frustrating, Sandoval said.

“Vaccines work and they save lives, but there are political decisions that are wrong,” Sandoval said. “This type of action, such as the loss of vaccines, negatively affects confidence in vaccines that we know work.”