Twenty years ago, the first in the director’s web-slinger trilogy set the course for the modern superhero film – but none of its descendants have ever matched it, writes Kambole Campbell

“With great power, there must also come great responsibility.” Through all of Spider-Man’s variations and different authors and artists, those final words from Amazing Fantasy #15 – the 1962 comic book that first introduced the spectacular superhero – remain the focal point of the story of Peter Parker, the teenage boy bitten by a radioactive spider that grants him arachnid-like powers – and Parker’s struggle to live up to that adage has remained the same throughout the decades since.

When it comes to Spider-Man’s multiple big-screen iterations, though, the films that have perhaps best embodied this timeless quest are Sam Raimi’s early Noughties Spider-Man series – with Tobey Maguire as the eponymous web-slinger – a trilogy as swooningly romantic and tragic as it is high-flying and colourful. Twenty years ago this week, the first of the films opened in US cinemas, and it was both instrumental to – and really, completely unlike – the superhero films that followed it.

Raimi’s Spider-Man was really invested in the human drama of the clash between Peter Parker’s two identities (Credit: Alamy)

On the one hand, Spider-Man’s huge box-office success was a revitalizing shot in the arm (or bite on the hand) for the entire comic-book movie genre. Yet it also now feels somewhat quaint in the face of the all-consuming industry that has flourished in its wake, where every Marvel or DC film is but a cog in a giant machine requiring viewers to buy into multiple franchises that are constantly crossing over.

Before the film’s release in 2002, there were already other successful superhero series in motion, such as the X-Men and Blade series, but as James Hunt of the Cinematic Universe podcast notes, it was Raimi’s Spider-Man films that created the rough shape of what comic-book movies are now, for all the good and bad that entails. What set it apart right away was the “light (if heightened) tone”, Hunt says, one that “tracks through to the likes of Iron Man, Captain America and Thor. While Raimi was making upbeat family movies, other companies were off making dour superhero action so that they could avoid accusations of campness.”

A true comic-book movie

Where these other franchises sought to “modernise” superheroes and make them cooler, (but were more in step with a “1990s action movie tradition with a heavy dose of post-Matrix influence” as Hunt says) Raimi instead leant into the classic cadence of the original 1960s “Silver Age” comics of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko and embraced their dorkiness as well as their pathos. With their forever youthful characters and continued use of the same iconography, superhero comic books are basically timeless by design, and Raimi’s films themselves sought this sense of timelessness, of being able to leap (or web swing) into a story that doesn’t age.

Despite making his name with the extreme gore of The Evil Dead franchise, Raimi’s take on Spider-Man had a classic feel. It was that of someone who had grown up reading classic Marvel Comics, and whose love for the source material extends outwards into every element of the film, from the colourful Spidey costume ripped straight from 4-colour print pages, to the old-fashioned feeling of its central romance between Spider-Man/Peter Parker and his classmate Mary Jane Watson. It truly has the feel of a comic book, in a way that superhero movies haven’t since.

Raimi’s vision for the film was truly focused on the human drama of a young man being torn between two worlds rather than superhuman ass-kickings or franchise course-setting

Why Raimi’s film also holds up so well is that amongst all the superhero spectacle, it remains decidedly humanist: Parker’s Uncle Ben and Aunt May (played by Cliff Robertson and Rosemary Harris) leave as much impact with their parental wisdom as Willem Dafoe does with his theatrics as the villainous Green Goblin. It’s all told with an unabashed earnestness that, as Hunt points out, gave it more in common with Richard Donner’s 1978 Superman film, starring Christopher Reeve, than its edgier contemporaries – a parallel that was also apparent in the film’s brightly coloured romanticism and the title hero’s bespectacled, mild-mannered alter ego with red and blue spandex under his shirt. There’s perhaps something of Tim Burton’s Batman movies, too. in its pulpiness and flirtations with the macabre – as well as the recruitment of composer and one-time frontman of New Wave band Oingo Boingo, Danny Elfman, for the operatic touch of his incredible score.

At a time when too many comic-book adaptations choose to deploy a defensively ironic tone, complete with lots of self-conscious quipping, that sincerity feels particularly refreshing – and it’s a quality that was thrown into sharper relief by the recent, soullessly meta Spider-Man: No Way Home, which brought together three different live-action iterations of the friendly neighbourhood wall-crawler, with the latest Spidey Tom Holland joined by Maguire and Andrew Garfield. By contrast, Raimi himself notes in a recent Variety interview looking back on his trilogy: “I wanted to make sure we weren’t making an ‘in on the joke with the audience’ presentation… I never wanted to have that separation for me and the material, or assume that the audience had it.”

The upside-down kiss between Maguire and Kirsten Dunst’s Mary Jane is both iconic and embodies the film’s old-school romanticism (Credit: Alamy)

Spider-Man also benefitted from Raimi’s distinct visual style in capturing that earnestness: it embodied a nostalgia for the comic books, which the MCU movies have tried and failed to emulate, having so often submerged the quirks of their directors in CGI and an interchangeable house style. It is uniquely goofy in its aesthetic and use of techniques like montage and superimposition: Peter Parker’s initial creation of the Spider-Man costume plays out through a shifting collage of images, the silver screen’s answer to the visual language of comic books. Indeed, there is a sense that Raimi, more than most directors, has an innate understanding of the comic-book mythos: you can practically see the yellow boxes surrounding the narration by Peter Parker that bookends the film.

It is interesting that Raimi has himself now joined the MCU as director of Doctor Strange In The Multiverse of Madness, released this week. What’s gratifying is that, as critics have suggested, his directorial instincts are still as striking, even in a franchise known for its oppressive visual sensibilities that typically nullify even the strongest cinematic voices. Though the film is still beginning from that familiar MCU template, Raimi manages to bring to the franchise the gleefully goofy visual flourishes he brought to Spider-Man, as well as his talent for horror comedy.

For Raimi, the Spider-Man gig was the culmination of a period in which he had begun to apply his B-movie horror training to a wealth of different genre films, from postmodern western The Quick and the Dead (1995) to neo-noir A Simple Plan (1998). Before his hiring, Spider-Man had been a project stranded in production hell, as it changed hands between directors including Tobe Hooper, James Cameron (who came up with Peter’s gross organic webs), even Harry Potter’s Chris Columbus at one point.

A different kind of superhero

If Raimi was a maverick choice for a project like Spider-Man, then his casting was equally so: against expectations, he picked Maguire to be the lead, having been impressed by his performance in The Cider House Rules, and enamoured by his gentle demeanour on sceeen, that was in opposition to the macho-ness of his superhero contemporaries. Maguire’s casting is emblematic of where screenwriter David Koepp and Raimi’s vision for the film was truly focused – on the human drama of a young man being torn between two worlds rather than superhuman ass-kickings or franchise course-setting. It’s all about the essence of Spider-Man as a character, in Peter’s struggle with his two personas; as Raimi has said, his film was about “investing wholly into [Parker’s] heart and matters of his soul”. The human side of the character is made to matter perhaps even more than the superhero fantasy, Peter’s flaws being the basis of his appeal: his failures are relatable, while his constant work to be a better person in his late uncle’s memory is inspiring.

The upside-down kiss between Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst is both iconic and embodies the film’s old-school romanticism

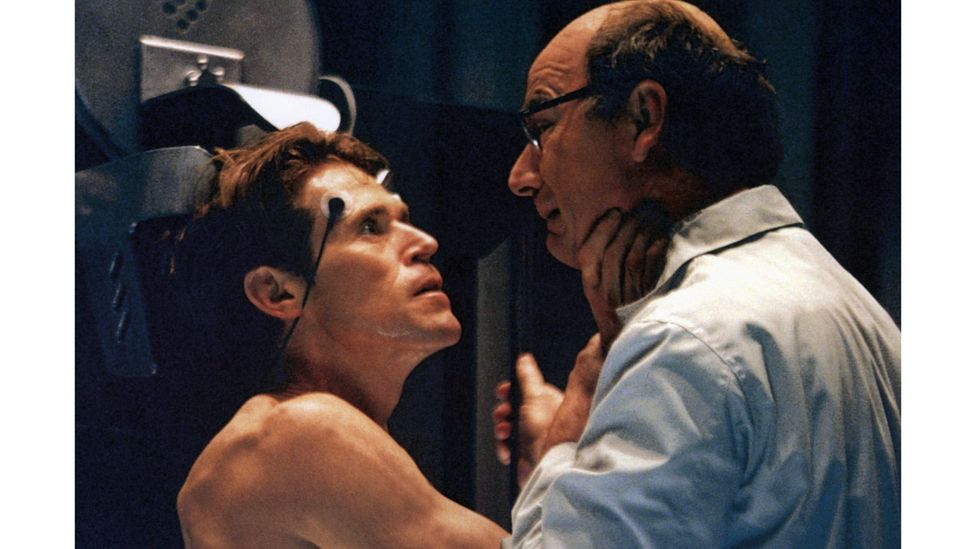

Meanwhile the tension of Peter’s dual lives is evident even in the costume design, with the eye lenses of Spider-Man’s outfit designed to resemble a mirror. They make for one of the film’s most striking shots, where he is seemingly forced to choose between saving Mary Jane or a cable car full of children, the person he loves or the citizens he has sworn to protect – with each of the imperilled parties reflected in a different eye (this being Spider-Man, he of course decides to save both, against all odds). It’s one of many instances of “the struggle of a dual identity rendered in thrilling visual metaphor” as Daniel Dockery, senior writer at entertainment website Crunchyroll, puts it. Peter Parker’s duality is then itself mirrored in Dafoe’s performance as Norman Osborn, the wealthy Manhattanite who transforms into the Green Goblin, like a modern-day Gollum – but where the key transformative special effect is not CGI but the elasticity of Dafoe’s face. His is an incredibly physical performance, all big theatrical expressions and movements, where Maguire instead retreats inward.

Another thing at the core of the film’s success is its heart-rending romance. Though people might first associate the character with high-flying action, there is a particular attachment to affairs of the heart in the Spider-Man mythos – Peter Parker and Mary Jane might be one of comic books’ most beloved couples. And while the Andrew Garfield and Tom Holland Spidey eras are also full of longing, the romance feels strongest in the presentation of the Raimi/Maguire films.

Willem Dafoe is incredibly expressive as the villain, with the elasticity of his face helping to enact his transformation into the Green Goblin (Credit: Alamy)

Whole articles could be dedicated to the MTV Award-winning upside-down kiss between Maguire and Kirsten Dunst’s Mary Jane, but in short, it’s both iconic and embodies the film’s old-school romanticism: it’s notable too that Parker’s narration is as much focused on Mary Jane as the life he leads as Spider-Man. In Raimi’s conception, this Mary Jane (stepping into the shoes of canonical first girlfriend Gwen Stacy, whom Dunst initially thought she was being cast for), is a simpler, more down-to-earth take on her character in the comic books: the archetypal girl next door, but also someone with insecurities, familial struggles and financial problems of her own unfolding on screen.

Mary Jane is also something like the Lois Lane to Spider-Man’s Superman – someone who as the result of constantly being in harm’s way, begins a romantic relationship with the mysterious symbol before the man himself, again furthering the estrangement Peter feels between these two parts of his life. That tension between his two selves, the timid geek and the Amazing Spider-Man, the lovelorn teenager and action hero, his growing pains and that oft-mentioned responsibility, all lead into one of the most impressively miserable blockbuster endings of its time – one where even when the hero saves the day, he loses still. For while Mary Jane declares her love for Parker, he feels forced to reject her in order to keep her safe from his perilous double-life, that she still doesn’t know about. It’s an ending that is quintessential Spider-Man, and also rounds off the film in a way that allows it, crucially, to stand on its own – something that feels particularly rare when nowadays seemingly every superhero flick requires homework, and has to have end-credit cameos from characters trailing other movies to come.

A heady mix of genres

Above all, it’s Raimi’s deft handling of various genres and tones that makes the film such a rich tapestry. Empire’s associate editor Amon Warmann agrees: “my favourite superhero movies are often the ones which have an excellent tonal balance, and Spider-Man achieves that masterfully,” he says. “There’s a lot of funny humour and purely entertaining heroics, but when the film gets serious, those moments hit hard too.”

Indeed, there are so many disparate elements to Spider-Man that shouldn’t make sense when blended together, but somehow work perfectly: Raimi’s aforementioned horror roots revealing themselves following Peter’s fateful radioactive spider-bite feels like a huge contrast to the absurd comedy of the appearance of wrestler “Macho Man” Randy Savage as “Bonesaw McGraw” in the formative cage-match that solidifies Spider-Man’s identity. As Hunt says: “Raimi was the one director who really understood that Spider-Man is simultaneously a romance, a comedy, a horror, a sci-fi and an action franchise, and he shot it like it was all of those things with a coherence we’ve not seen since”.

Raimi has now entered the MCU with this week’s Dr Strange in the Multiverse of Madness – and managed to retain some of his directorial style (Credit: Alamy)

It’s all tied together with that heightened visual style that the trilogy became known for. Though the VFX shows its 20-year-age a little, it hardly matters when the stylisation still feels so lively and striking, the camera swooping along with the wall crawler as he swings through the city, movements that cinematographer Bill Pope would perfect in Spider-Man 2. Even with this use of digital effects and animation, there is also a heartening dedication to making the action feel as authentic as possible – Willem Dafoe did many of his own stunts and insisted on being the one in the costume so as to best capture Green Goblin’s body language. Even the moment when Peter miraculously catches food falling through the air on a cafeteria tray was done for real. In Raimi’s hands, the most menial sequences feel more meticulously choreographed and ultimately more lively than the detachable, washed-out set pieces that accompany much MCU fare. Spider-Man’s final showdown with the Green Goblin also feels a lot more personal, even brutal, than we are now used to from superhero films: Warmann notes how Elfman’s score fades into the background, allowing “each punch [to] land harder”, as Raimi’s camera “never cuts away from the carnage”.

Raimi’s Spider-Man series did not end in glory: Spider-Man 3 (2007) was (in this writer’s opinion, somewhat unfairly) maligned, and plans for a fourth film were canned after studio conflicts. But amid today’s comic-book filmmaking, the trilogy still truly stands apart, embodying qualities that have since been lost. “Raimi’s films would be some of the last of their kind in the superhero genre,” agrees Dockery. “They bear a sincere, aw-shucks mentality and a distinct storytelling and visual style that is often lost in the machinations of franchising. To return to them is a reminder that, just as Spider-Man is constantly ‘trying to do better’, so can cinema in this form.”

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.