ExoMars mission, of which the £840m British-built vehicle was part, depended on a Russian Proton rocket

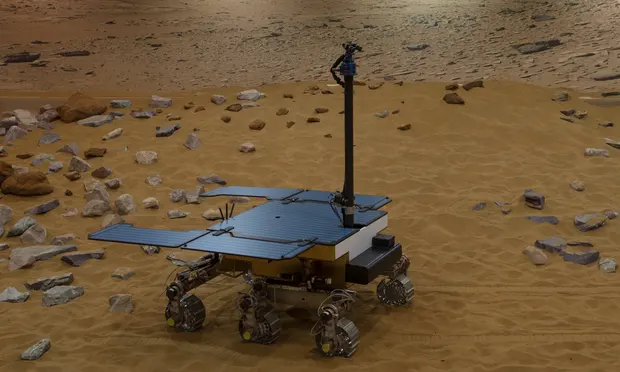

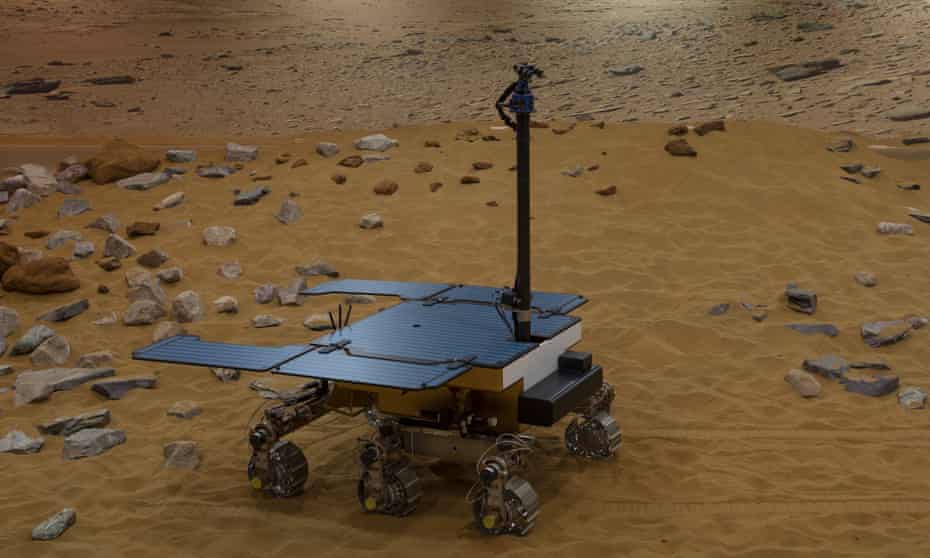

It has cost £840m to develop and taken 15 years to build. But now fears are mounting that the British-built robot rover – which was to have flown on Europe’s ExoMars mission in September – may never make it to the red planet.

The craft was to have drilled deep below the Martian surface to collect samples that could bear signs of past or present life, but had its launch on a giant Russian Proton rocket postponed last month after the invasion of Ukraine.

At best, the rover – built in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, and financed by the European Space Agency – will have to wait two more years, when the next window opens for sending a spacecraft to Mars. However, some astronomers fear that prospects for the rover, named after the British DNA pioneer Rosalind Franklin, now look grim. If delays continue, it could ultimately be mothballed, scientists have warned.

“It is inconceivable that we can work with Russia under present circumstances, and that attitude is going to last a long time,” said astronomer Professor John Zarnecki of the Open University. “This could delay ExoMars for the rest of the decade. By then, its technology will be getting dated.”

The alternative would be to find another launcher. However, such a move poses other problems. Russia was also supplying the Kazachok lander that was to settle the Rosalind Franklin safely on the planet’s surface. “First, a huge parachute would have decelerated the craft as it descended through the Martian atmosphere. Then Kazachok’s retro rockets would have further slowed it down so the rover could land gently,” said Professor Andrew Coates, of University College London.

“It is an extremely tricky, complex manoeuvre and designing a replacement landing system will not be easy,” added Coates, who is principal investigator for the rover’s panoramic camera experiment.

Previous Martian rovers have managed to scrape soil samples from a depth of only about 6cm. “That is the key feature of this mission,” said Coates. “We will be bringing samples from depths of two metres, where any signs of life are going to be better protected from the cosmic rays that batter Mars’ surface.”

Several dozen planetary scientists in Britain have been involved in work on ExoMars – including Áine O’Brien, at Glasgow University.

“It’s a weird experience for all of us,” she told the Observer. “We are sad because of what has happened to our work and the chance of being involved in searching for life on Mars but you also feel guilty for feeling sad – because, among everything else, it’s a really minor setback compared with what the people of Ukraine are suffering.”

While some scientists remain relatively optimistic that Europe and Russia might cooperate in space again, others remain doubtful.

“If it ends up being postponed until the end of the decade, as we hunt for new launchers and develop new landing systems, then the mission will all start to look old,” said Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society. “That is why there is speculation now that it might never fly.”

This view was backed by O’Brien: “In the end, we may have to cut our losses and concentrate on other Mars missions.”

Nor is ExoMars likely to be the only casualty of the invasion of Ukraine. Russia provides relatively cheap but powerful rockets that have been used to launch many European missions in the past. Immediate victims of the suspension of future launches will include two Galileo navigation satellites , while The ESA’s EarthCare science mission, developed in cooperation with the Japanese space agency, Jaxa, and the Euclid infrared space telescope will also be affected.

More perplexing is the likely impact on the International Space Station, which relies on a Russian propulsion system to boost away from Earth as its orbit decays and to move it to avoid space debris. Should Russia pull out of the ISS, then the vast orbiting laboratory would slowly spiral lower and lower until it crashed.

This threat was recently made explicit by Dmitry Rogozin, the head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos. Russia would determine on its own “how long the ISS will operate”, he told the country’s state news agency, Tass.

… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are turning to the Guardian for open, independent, quality news every day, and readers in 180 countries around the world now support us financially.

We believe everyone deserves access to information that’s grounded in science and truth, and analysis rooted in authority and integrity. That’s why we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This means more people can be better informed, united, and inspired to take meaningful action.

In these perilous times, a truth-seeking global news organization like the Guardian is essential. We have no shareholders or billionaire owner, meaning our journalism is free from commercial and political influence – this makes us different. When it’s never been more important, our independence allows us to fearlessly investigate, challenge and expose those in power. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. If you can, please consider supporting us with a regular amount each month. Thank you.