Earlier this month, a group of archivists in the western Indian city of Mumbai recovered what now appears to be the only surviving link with the first Indian talking film.

Led by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, an award-winning filmmaker, archivist and restorer, they stumbled upon a vintage machine which had been used to make prints of Alam Ara (Ornament of the World), the 1931 film that has disappeared.

The Chicago-made Bell & Howell film printing machine was lying idle in a rented shop selling saris. Originally owned by the film’s producer and director Ardeshir Irani, the machine was later purchased by Nalin Sampat, who also owned a film studio and a processing laboratory in Mumbai.

“This is the only surviving artefact of Alam Ara. Nothing really survives of the film except this,” says Dungarpur.

The Sampats had paid 2,500 rupees in 1962 to buy the machine. Their lab continued to print films, mainly produced by the state-owned Films Division, on it until 2000. “It was just another printing machine but held a lot of emotional value. We stopped using it after cinema went digital,” Sampat says.

For the past decade, Dungarpur – he runs the Film Heritage Foundation, a Mumbai-based non-profit film archive – has been trying to find a copy of Alam Ara without success. He even gave out a call on social media. One tip led to enquiries with a film archive in Algeria, which reported it had a number of old Indian films. But the archive asked him to come and check, which Dungarpur has not been able to.

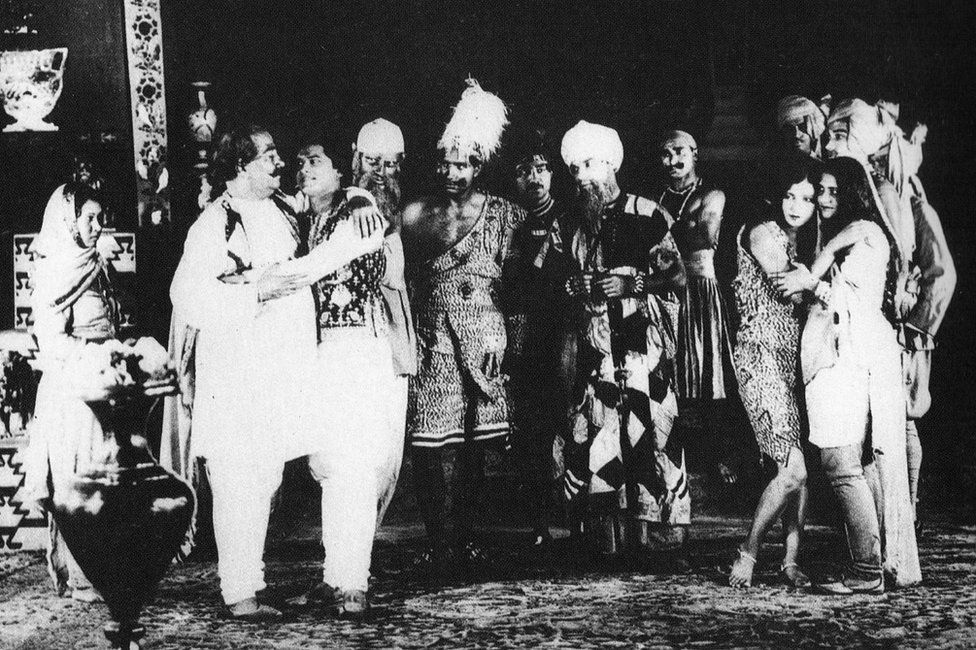

Another tantalising clue is the film archives in Iran. Around the time Irani was shooting Alam Ara in Mumbai, his studio was also making Lor Girl, the first talking film in Persian language. “Irani used the same background actors wearing the same costumes for both Alam Ara and Lor Girl. Alam Ara has disappeared. Lor Girl is available in the archives in Iran,” says Dungarpur.

India’s most-well known film scholar and archivist PK Nair once said he refused to believe that Alam Ara is “permanently lost”. Nair, who died in 2016, himself went hunting for the film and met surviving members of the Irani family.

One member of the family told him that “a couple of reels must be lying around somewhere”. Another said he “had disposed off three reels after extracting silver from it”. Alam Ara was shot on nitrate film, which has higher silver content than other film bases. It is possible, says Dungarpur, that the films had been destroyed after stripping them for silver to earn money when the family fell upon bad times. “Such was the case with countless other films too”.

India has a shoddy record in preserving films. Most of the 1,138 silent films made between 1912 and 1931 do not exist anymore. The state-run film institute in Pune has managed to archive 29 of these films. Prints and negatives have been found dumped in shops, homes, basements, warehouses and even in a cinema hall in Thailand. Filmmaker Mrinal Sen found prints of an old Bengali talkie lying around in an old house where he was shooting a film in 1980.

But Alam Ara may be the most important film which has been lost. Inspired by the 1929 Hollywood romantic drama Show Boat and drawn heavily from theatre as many early talking films were, the film, based in a mythical kingdom, was described as a “swashbuckling tale of warring queens, palace intrigue, jealously and romance”. The British Film Institute called it a “romantic drama centred around the love between a prince and a gypsy girl”.

The 124-minute film was shot behind closed doors to keep out the noise which could seep into the sound. The studio where it was shot overlooked Mumbai’s railway tracks, so the crew shot at night when the trains did not run and the floor did not shudder from the vibrations.

Since there were no boom mikes to record sound, microphones were placed in “incredible spaces” around actors – who spoke in Urdu and Hindi – in a way that they were hidden from the camera. Musicians climbed on or hid behind trees and played their instruments for the soundtrack and songs. Most importantly, the film featured Wazir Mohammed Khan, playing an ageing mendicant, who sang the first Indian film song.

Ardeshir Irani told an interviewer that he had picked up the basics of sound recording from a “Mr Deming, a foreign expert, who had come to Bombay (now Mumbai) to assemble the machine for us”. Mr Deming charged the producers 100 rupees per day – “a large sum for those days which we could ill afford, so I took upon myself to record the film” with the help of others, he said.

The film released on 14 March, 1931, and was sold out for weeks. Police had to control excited crowds outside theatres. One critic said the “rather inconsequential plot served as little more than a string to hold together umpteen song-and-dance numbers”. The film’s heroine, Zubeida, who combined “innocence with eroticism”, was a huge draw.

Sitara Devi, a celebrated Indian dancer who watched the film, recalled it was a “huge sensation”. “People were used to seeing silent movies after reading the title cards. Now characters were speaking. People were saying in the theatre where is the sound coming from?,” Devi told Dungarpur.

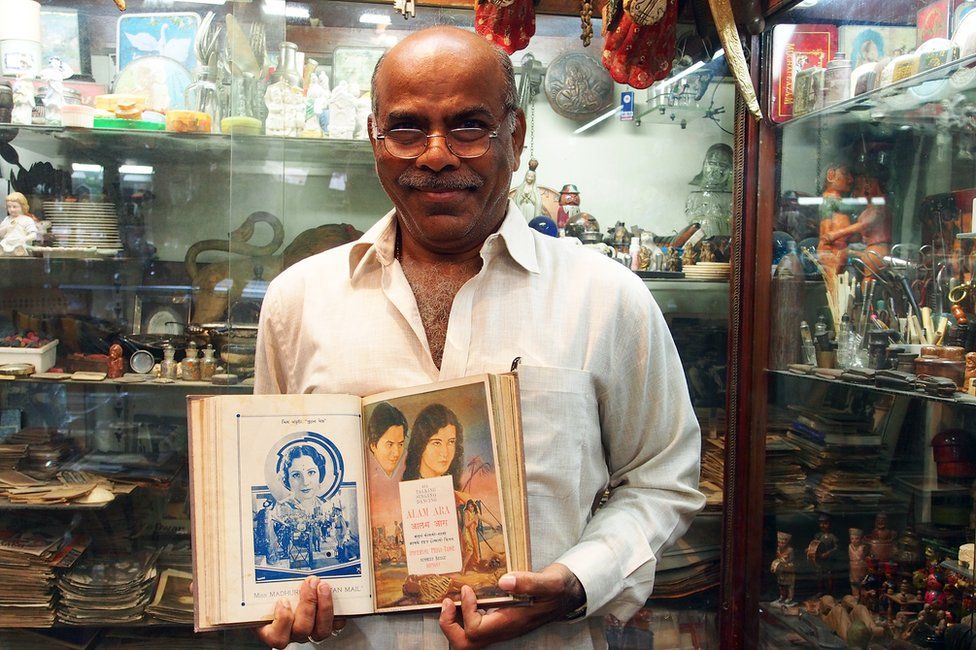

So what remains of Alam Ara are a few stills, posters and a promotional booklet. Shahid Husain Mansoori, who owns a shop selling film props in Mumbai, possesses the booklet. “It has been been with us more for some 60 years now. I hear it’s the only one available. Nobody really knows the value of these things today”.