Researchers studying human remains from Pompeii have extracted genetic secrets from the bones of a man and a woman who were buried when the Roman city was engulfed in volcanic ash.

This first “Pompeian human genome” is an almost complete set of “genetic instructions” from the victims, encoded in DNA extracted from their bones.

Ancient DNA was preserved in bodies that were encased in time-hardened ash.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

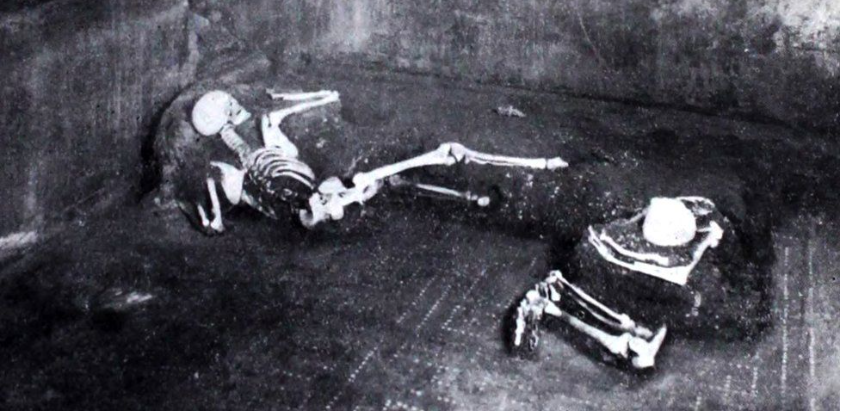

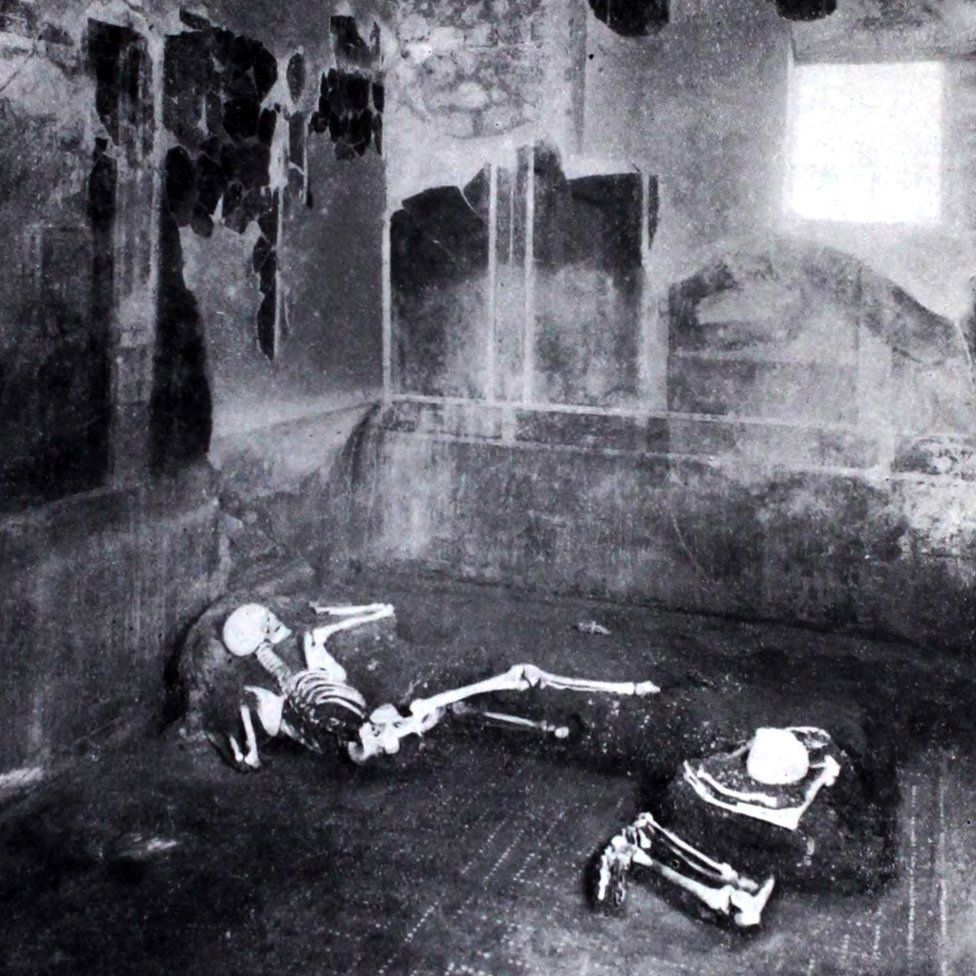

The two people were first discovered in 1933, in what Pompeii archaeologists have called Casa del Fabbro, or The Craftsman’s House.

They were slumped in the corner of the dining room, almost as though they were having lunch when the eruption occurred – on 24 August 79AD. One recent study suggested that the huge cloud of ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius could have become lethal for the city’s residents in less than 20 minutes.

The two victims the researchers studied, according to anthropologist Dr Serena Viva from the University of Salento, were not attempting to escape.

“From the position [of their bodies] it seems they were not running away,” Dr Viva told BBC Radio 4’s Inside Science. “The answer to why they weren’t fleeing could lie in their health conditions.”

Clues have now been revealed in this new study of their bones.

“It was all about the preservation of the skeletons,” explained Prof Gabriele Scorrano, from the Lundbeck GeoGenetics centre in Copenhagen, who led the study. “It’s the first thing we looked at, and it looked promising, so we decided to give [DNA extraction] a shot.”

Both the remarkable preservation and the latest laboratory technology allowed the scientists to extract a great deal of information from a “really small amount of bone powder”, as Prof Scorrano explained.

“New sequencing machines can [read] several whole genomes at the same time,” he said.

The genetic study revealed that the man’s skeleton contained DNA from tuberculosis-causing bacteria, suggesting he might have had the disease prior to his death. And a fragment of bone at the base of his skull contained enough intact DNA to work out his entire genetic code.

This showed that he shared “genetic markers” – or recognisable reference points in his genetic code – with other individuals who lived in Italy during the Roman Imperial age. But he also had a group of genes commonly found in those from the island of Sardinia, which suggested there might have been high levels of genetic diversity across the Italian Peninsula at the time.

Prof Scorrano said there would be much more to learn in biological studies of Pompeii – including from ancient environmental DNA, which could reveal more about biodiversity at the time.

“Pompeii is like a Roman island, ” he added. “We have a picture of one day in 79AD.”

Dr Viva added that every human body in Pompeii was “a treasure”.

“These people are silent witnesses to one of the most well-known historical events in the world,” she said. “To work with them is very emotional and a great privilege for me.”