There is a jaw-dropping line in the first episode of the new season of Borgen, the internationally popular Danish drama returning after a nine-year lapse. Birgitte Nyborg (Sidse Babett Knudsen) who became Denmark’s first woman prime minster in season one, is now foreign minister, grappling with the fallout of an oil discovery in Greenland, a Danish territory. Angrily arguing that Denmark cannot do business with a drilling company whose investors include a Russian oligarch, she cites the fact that “Russia is being internationally sanctioned for attacking Ukraine.” But the show was shot long before Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February. Did they reshoot the scene? Loop in that line? Does Borgen employ prophets instead of writers? No to all of that, Adam Price, the series’ creator, tells BBC Culture. “She’s talking about the annexation of Crimea, she’s talking about 2014. But of course, now nobody can see that scene without thinking that it must be the current crisis between Russia and Ukraine.”

More like this:

– The sci-fi show that terrified Britain

– The murders that shook US Mormons

– The French TV series that stormed the world

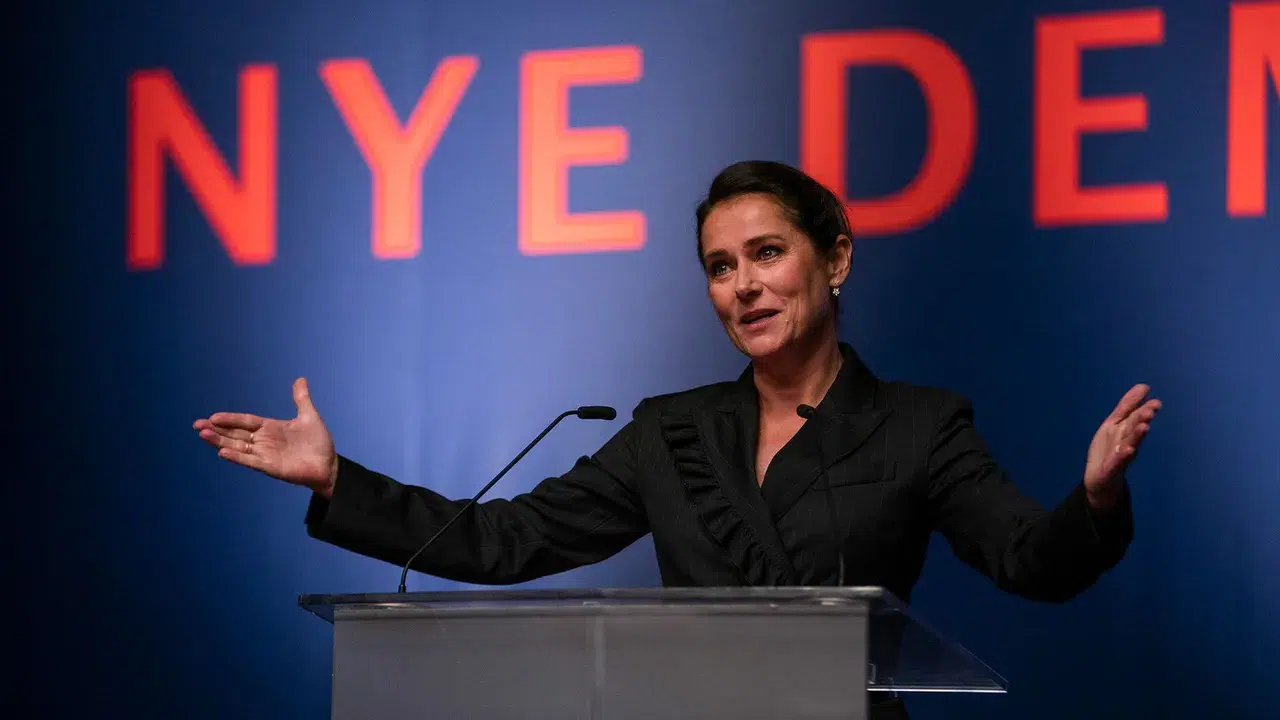

Such sharp-eyed, uncanny timeliness is just one of many reasons Borgen continues to be the best political drama ever. The West Wing, for all its attention to political detail, is full of gushy idealism backed by soaring, manipulative music. House of Cards, both the original UK version and the US remake, are unremittingly cynical. Borgen stands apart from any other in creating a perfect balance. Birgitte is idealistic, but also a hard-nosed political realist. The show’s plots are a vibrant mix of personal dilemmas and intricate political horse-trading, with themes touching on feminism and the media, set amidst all the ambition and deceit that swirl around any country’s government.

Birgitte’s character combines idealism with the pragmatism needed for politicking (Credit: Netflix)

Few shows have transferred to other countries so well or depicted politics so authentically. When Borgen became a global phenomenon in its first three seasons, from 2010-2013, its fans included Nicola Sturgeon, First Minister of Scotland, and the journalist Emily Maitlis, formerly of the BBC’s Newsnight, and author of Airhead: The Imperfect Art of Making News. Borgen gained an even larger audience when those seasons arrived on Netflix in 2020, and the new instalments, on Netflix from 2 June, will reach 190 territories.

It was a show that talked to vulnerability as well as power, which is what made it so attractive – Emily Maitlis

At the centre is Birgitte – humane, relatable, yet a political mastermind – and the inextricable theme of power. Speaking about the previous seasons, Maitlis tells BBC Culture, “The way you found Birgitte in the seat of power but wrangling with all the usual complicated stuff around marriage and children and school drop-off was so brilliant. It was a show that talked to vulnerability as well as power, which is what made it so attractive, I think.” She’s right.

“Borgen has always been a study of power, and how power affects the characters on the show,” Price says. The new season even has the subtitle Power and Glory, and raises the question of how far Birgitte will go to hold onto those things. After decades in high-level positions, she has inevitably changed, Price says. “She has made some very crucial and I would say dangerous choices, professionally and privately.” No wonder the epigraphs that have always begun each episode are so often from Machiavelli. The world has changed, too, and the new season remarkably manages to keep its old DNA while adding timely themes, including social media, and emphasising global politics.

Birgitte’s family life suffered after she became Danish prime minister (Credit: Netflix)

Birgitte became Denmark’s first woman prime minister at the start of the season one, happily married with two children, and was divorced by the end of that season – not unrelated events. The cost of ambition and success for women has always been a central theme, so gracefully integrated into Birgitte’s character that it never lands with a thud. By the end of season three she had started a new political party, had a new love interest, and was about to become foreign minister. Gazing at the Danish Parliament – Borgen translates as The Castle, the nickname for that building – she lovingly said, “It’s my second home.”

Now nearly 10 years on, as foreign minister again she is dealing with a prime minister from an opposing party, a woman a decade younger than herself. This prime minister has a prominent social media presence, posting Instagram photos with the hashtag #TheFutureisFemale, a public relations ploy that she uses to try to rope Birgitte into the sham illusion of sisterhood. Behind the scenes the two women are fierce rivals, endlessly at odds, trying to use each other. One of the bracingly authentic aspects of Borgen is how rarely it indulges in dreamy wishful thinking, whether about sexism, media or politics.

Capturing reality

There is no end to the show’s clear-eyed realism – at 53, Birgitte is having hot flushes, surreptitiously changing her blouse between meetings – and there is no explanation of the time gap since season three. One of Borgen’s strengths is that it doesn’t insult the audience by stating what we can intuit. Obviously things didn’t work out with Jeremy, her British boyfriend, who is gone and apparently forgotten.

Alone, her children grown, Birgitte is solely focused on her work, which gives the season its main, very volatile plotline. (Ukraine is more of a blip.) When the oil is discovered, Birgitte faces an ethical dilemma. She has campaigned on an environmental agenda and is opposed to drilling for fossil fuels. But the drilling would be worth $200bn, much of it coming to Denmark, and the prime minister wants to move ahead for economic reasons. Price says he appreciates the tension of this scenario, where “You challenge the tragedies of climate change with the gaining of riches of this magnitude.” In some alternate, idealistic series Birgitte might have resigned on principle. Not here. Price himself sounds very pragmatic, with an explanation for every setting and turn of character, including how Birgitte experiencing menopause speaks to her character. “She is very controlling, but she cannot control the nature of her body,” he says.

Katrine Fonsmark (played by Birgitte Hjort Sørensen) is a key character in the new series (Credit: Netflix)

Kasper Juul, Birgitte’s former press secretary, is the only major character from previous seasons missing. But the show has found an engaging substitute to fill the slot of good-looking younger guy in Birgitte’s orbit. Asger Holm Kierkegaard (Mikkel Boe Følsgaard) is her supersmart, slightly insecure ambassador to the Arctic. He spends much of his time negotiating in Greenland, which allows the series to highlight that country’s beautiful, icy scenery as well as enter the world of whale hunting. Asger has his own romantic plot and his own ethical tussles.

And the journalist Katrine Fonsmark (Birgitte Hjort Sørensen) is now head of news at TV1. To reveal more about her trajectory would be too much of a spoiler, so let’s just say she is severely challenged, by her own staff and, in an especially topical and realistic subplot, by blowback from social media. Her story adds an unexpected, potentially controversial wrinkle to the theme of women and power.

All the plotlines lead back to Birgitte, who once more finds ingenious ways out of a political morass. Borgen never loses sight of the dramatic elements, another reason it is so deep and satisfying. As Torben Friis (Søren Malling), previously TV1’s news director and now its political reporter, says this season when Birgitte lands in yet another political tight spot, “I can’t imagine how Nyborg will wiggle out of this one.”

Knudsen’s performance is nuanced and subtle (Credit: Netflix)

Birgitte is played by Knudsen with such depth of knowledge about the character that a simple glance or line can be a revelation. “I’m having the time of my life,” Birgitte tells Katrine about her single status. “No kids at home. No neglected husband.” But Knudsen subtly hints at the hollowness of that claim, at how much Birgitte might be convincing herself. Later she bluntly, and a little drunkenly, admits to Asger over dinner, “Becoming prime minister cost me my marriage and my family,” insisting that she would do it all again. No doubt she would, and Knudsen allows us to sympathise with the character’s choices without diminishing the price of her ambition.

That ambition is displayed as she shrewdly navigates issues that mirror the real world. Robert Saunders, professor of Geopolitics and International Relations at the State University of New York, studies politics and popular culture, particularly Nordic television, and the way television both reflects and anticipates reality. He tells BBC Culture, “In the field that I operate in Borgen is seen as the classic example,” because the show depicted Birgitte becoming the first female prime minister just months before Helle Thorning-Schmidt assumed that role in real life. Price has always said he was lucky in that timing. But the plot was also based on an astute sense of where the country was heading. If not Throning-Schmidt, then inevitably another woman would have arrived in that role soon.

A similar zeitgeist-catching dynamic is on display in this season’s focus on climate change and international relations. In real life, Greenland’s ice is melting even faster than scientists previously thought. And the Arctic is crucial geopolitically with the US, Russia and China all trying to assert influence. In trying to sort out the oil dilemma as foreign minister, Birgitte does a political favour for the US ambassador to Denmark and meets with the US secretary of state. She gets intelligence from the Chinese ambassador, and uses it to negotiate as she tries to outwit the Russians. All that happens in addition to the backstabbing in her own party.

People may disagree, but often they come to an agreement, however begrudging it is, and move forward – Robert Saunders

Because the war in Ukraine has understandably pushed much other news aside, the omission of any reference to it does give the new season a slightly skewed sense of reality. The show is timely when it mentions that an oligarch who is about to be sanctioned by the European Union has ties to the Russian president. (Vladimir Putin is never named; he doesn’t have to be.) Only one line lands in a jarring way, when we hear the outdated claim that the US is OK with Russia selling gas to European countries. But reality has rarely overtaken Borgen in that negative way. That too is by design. From the start, Price says, he has sought out subjects that have long life spans. The climate change problem will not be solved anytime soon, and it is easy enough to slide into the series’ reality-adjacent world.

The new season is centred on the issue of climate change, and its geopolitical implications in the Arctic (Credit: Netflix)

Price says his goal has always been to create “a fiction close to real life, but never just like real life.” That slight distance allows for an aspirational element. Throughout the seasons, Borgen’s bedrock of idealism is challenged and corrupted, but never completely disappears. Saunders says, “It’s interesting for me, as someone from the United States who sees how caustic our political system is, to see a political system on display where it’s not that way. This is reflective of Danish society. People may disagree, but often they come to an agreement, however begrudging it is, and move forward.”

Maitlis recalls seeing the journalists on the show and wondering, “Should we be able to get the PM any night as they swing by the [television] studio to explain a policy? It seems to have so little relation to British politics right now – just the access to politicians is amazing – that I think I would watch with awe at the idea that might be happening elsewhere.”

So close and yet so far– that delicate positioning also helps explain why Borgen translates so well to political systems that are vastly different from Denmark’s. As Price says, “If you just step back one or two steps, basically the mechanics of power are the same.”