Citing ‘unfulfilled expectations’, Prague considers leaving China’s 16+1 investment club for Central and Eastern Europe.

Prague, Czech Republic – The Czech Republic is considering an exit from China’s 16+1 investment platform for Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

The move could be a boost for the government’s pledge to reassert Prague’s Western orientation, but it also risks political and economic blowback from Beijing.

A resolution calling for the country to quit the 16+1 mechanism has been passed to the Czech foreign ministry and government after parliament’s foreign affairs committee unanimously approved it in mid-May.

There is little question that foreign minister Jan Lipavsky, long a China hawk, favours the motion. He claims that despite grand promises, the Czech Republic has seen little investment delivered.

“The main initiatives of the 16+1 format – economic diplomacy and promises of the large investment and mutually beneficial trade – have not been fulfilled, even after a decade,” he said in comments sent to Al Jazeera via a spokesperson.

These “unfulfilled expectations are leading us to reconsider our participation”, he confirmed.

Launched in 2012, the platform was supposed to secure political and economic influence inside the European Union for Beijing, amid suggestions that massive investment and trade would follow for CEE’s post-communist states.

However, little has been delivered, prompting complaints that the promises of shiny new roads and bridges have become meetings and forums.

Some Czech officials like to point out that investment flows from Taiwan are larger than those stemming from China.

This has seen the platform condemned as a “zombie”. Lithuania called for it to be put out of its misery when it walked away last year, claiming China is using the mechanism to divide Europe.

Political gesture

But although barely functioning, some Czech officials still see the platform as “a means to maintain bilateral relations with China”, Richard Q Turcsanyi, programme director at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies, told Al Jazeera.

Talk of leaving is therefore “a political gesture”, he said, and part of a long domestic struggle over foreign policy.

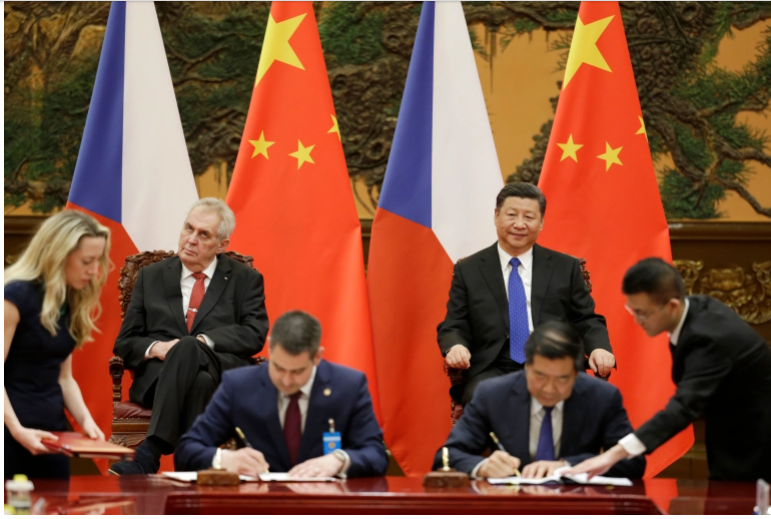

Despite the country being a member of the EU and NATO, Czech President Milos Zeman has for years sought to pull Prague closer to China and Russia.

However, the populist head of state has been weakened by the lack of investment, as well as numerous diplomatic spats with Beijing and Moscow in recent years.

Relations with China reached new lows two years ago when Beijing officials threatened that the Czechs would “pay a heavy price” as Milos Vystrcil, the head of the upper house Senate, led a delegation to Taiwan in 2020.

Since that episode, “China has not been perceived as a reliable partner”, Ivana Karaskova, an expert on Chinese policy at the Association for International Affairs, a Prague-based think-tank, told Al Jazeera.

A full-blooded rejection of Zeman’s Eastern push has been under way since Prime Minister Petr Fiala’s centre-right government came to power in November last year, pledging to reassert the Czech Republic’s Western orientation.

That agenda has only gathered pace due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The current Czech government has announced the intention to put our relations with China under review and revision,” said Lipavsky. “Our approach to 16+1 is a part of this process.”

Little to lose

Lipavsky, the foreign minister, did not respond to questions regarding the potential consequences.

Even if 16+1 is all but dead, Beijing is notoriously prickly about such slights, and some members of the Czech government appear cautious. Notably, Fiala has steered well clear of the debate, in public at least.

Therefore, there is certainly no guarantee that the government will approve the resolution, analysts agree, with government officials well aware of the blowback that Lithuania has been facing since its exit.

Also provoked by the opening of an office representing the Taiwanese government in Vilnius, China has all but cut economic ties with Lithuania.

However, with Czech-Chinese relations already in a poor state after the official Czech delegation visit to Taiwan, as well as Czech bans on Chinese involvement in public tenders to build 5G networks or new nuclear power stations, China hawks in Prague dismiss such threats.

Lipavsky said that despite the 16+1 platform, a deep deficit in the trade balance between the two countries remains. Therefore, he said, the Czech Republic has little to lose.

He is backed up by other senior members of the government.

“There’s not much to worry about in terms of backlash because relations are already in poor shape,” parliament speaker Marketa Pekarova Adamova and leader of the Top09 coalition party, told Al Jazeera. “Meanwhile, some Czech companies are already leaving China due to the deterioration of the market.”

Others point out that while the Czech Republic is too small to bother Beijing should it come to political or economic jousting, the EU – China’s second largest trade partner – certainly has sway.

“Retaliation from China is possible but it’s unclear what that would actually entail, and whether Beijing, which already has problematic relations with the EU over its economic coercion of Lithuania, is likely to want to escalate that further,” said Karaskova.

Putting down a marker

But some warn things are not so simple. They note that China has not only boycotted direct imports from Lithuania but all imports that contain Lithuanian components.

That makes Germany, whose industrial supply chains reach across CEE, an obvious target. With German exports to China totalling about €100bn ($107bn) last year, China hopes that its sanctions will persuade the EU’s biggest political and economic power to pull Vilnius into line.

The Czech Republic is similarly exposed, with its small and open economy even more heavily dependent on serving German industry.

“The idea that trade relations between Czech Republic and China are purely bilateral is very 20th century,” said Turcsanyi.

And it has been noted that such global networks raise awkward questions for the EU, especially as the bloc is busy stressing the importance of unity in the face of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

“The Lithuanian case forces the European Union to choose between tolerating the Chinese policies to protect its commercial interests or defending a small member country that is incapable of standing up to Beijing without the support of the other member countries,” said Heribert Dieter, a senior fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

Thus, the bid by the Czechs to exit a seemingly unimportant and defunct club could offer the EU the opportunity to put down an important geopolitical marker.

Political scientist Ivan Krastev recently asked whether, in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU might soon start to understand that its policy of using trade with authoritarian regimes as a vehicle to try to encourage democracy and cooperation has failed.

But there appears little optimism that the bloc is likely to change. “I’m sure the EU is already exerting diplomatic pressure on Prague to prevent it provoking Beijing,” Turcsanyi said.