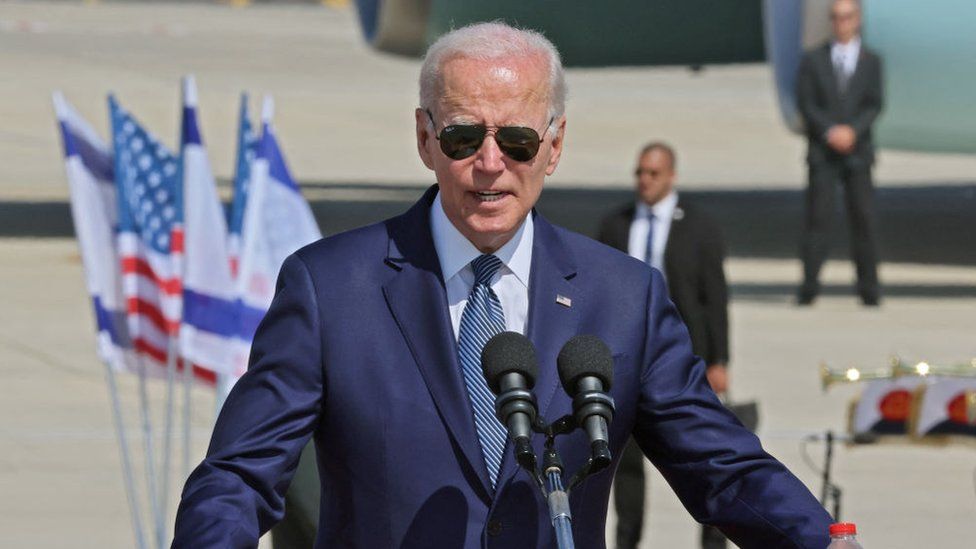

The day after the White House announced President Joe Biden’s trip to Saudi Arabia, a group of activists gathered to christen the street outside its Washington embassy “Khashoggi Way”.

They declared it would be a daily reminder to the diplomats “hiding behind those doors” that the kingdom’s government was responsible for the 2018 murder of the Saudi journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi.

And they denounced President Biden’s decision to meet the man fingered by US intelligence as having ordered the killing – Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, widely known as MBS.

“If you have to put oil over principles and expediency over values,” said Khashoggi’s fiancé Hatice Cengiz in remarks read at the event, “can you at least ask where is Jamal’s body? Doesn’t he deserve a proper burial?”

Why is this so controversial?

America’s decades-long dealings with Saudi Arabia have traditionally involved a trade-off between US values and strategic interests.

But President Biden explicitly emphasised human rights in the relationship, and now, as he bows to the political realities that shape it, he risks losing credibility on his values-driven approach to foreign policy.

The grisly murder of Khashoggi united both sides of Washington’s partisan divide in fury. A journalist and prominent critic of the crown prince, Khashoggi was killed and dismembered in Saudi Arabia’s Istanbul consulate.

As a presidential candidate, Mr Biden drew a categorical line in the sand, vowing to make the kingdom a “pariah” because of its grim human rights record. He used that sharp rhetoric to contrast himself with former President Donald Trump’s unreserved embrace of Saudi Arabia. Mr Trump once boasted he had “saved [MBS’] ass” from the outcry over Khashoggi’s death.

What led to this change in tune?

Once in power, Mr Biden suspended weapons sales and refused to talk with the crown prince. But there were doubts within the administration that this was a sustainable approach to the man who will probably soon become the Saudi ruler. A thaw had begun taking place over the past year, and Russia’s war in Ukraine pushed the US president to publicly become part of it.

Rising fuel prices were the driving force. The US appealed to the Saudis to pump more oil to help bring prices down. Riyadh initially rebuffed those requests. But just days before the president’s trip was announced, Opec Plus, the oil producer’s group of which Saudi Arabia is the de facto leader, approved a modest increase in production.

Analysts say there may be quiet agreement with the Saudis for a further modest uptick in output once a current quota agreement expires in September. But that’s unlikely to be mentioned on this trip.

The focus is more about longer term management of energy markets in these turbulent times, said Ben Cahill, an energy security expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“I think there is a sense in the White House that they need to be able to pick up the phone and have a constructive dialogue with lots of parties and in the oil world that starts with Saudi Arabia,” he said.

What does he hope to achieve?

But if the trip isn’t going to have an immediate impact at America’s gas stations, what outcome might make up for the president’s climbdown?

Mr Biden has played down the significance of any encounter with MBS, emphasising that he’s going to attend an Arab regional conference in Jeddah at which the crown prince will be present.

And he’s defended his decision to go by saying he’s acting partly at Israel’s request. He started his trip by stressing the importance of Israel becoming “totally integrated” in the region.

A big part of that is helping to normalise Israel’s relationship with Saudi Arabia, with a wider emphasis on closer Arab security ties with Israel. The idea is to coordinate air defence systems to deal with the threat of missiles from Iran and its allies.

The plan has gained momentum given stalled US efforts to revive the Iran nuclear agreement, Iran’s rapidly progressing nuclear programme, and an increase in regional missile attacks from Iran’s Yemen Houthi allies.

Paul Pillar of the left-leaning Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, called it a “military alliance against Iran”.

“The entire arrangement is based, certainly, from the Israeli point of view, but also from the Gulf Arab point of view, on hostility toward Iran,” he said.

However, no breakthrough announcement is expected. Saudi Arabia has some covert cooperation with Israel, but is holding back from going much further without movement on resolving the Palestinian conflict.

There are some small steps though: Saudi Arabia has expanded Israeli overflights in its airspace. It’s also expected to approve direct flights for Muslim pilgrims from Israel, and to guarantee shipping passage for Israeli vessels when two islands in the Red Sea are transferred over from Egypt.

What about the political damage?

In the United States, though, all eyes will be on the choreography of Mr Biden’s interactions with the Saudi crown prince.

The president has dismayed many in the human rights community, but his decision could also cost him political capital within his own Democratic party. Both argue that the only way for him to turn the trip into a “win” is to substantively raise human rights concerns.

They are urging him to press for the release of de facto political prisoners and the lifting of travel bans and other restrictions on activists. They also want him to publicly repeat the demand that Khashoggi’s killers be held to account.

And in a joint letter the chairs of six House committees called on the president to continue suspending offensive support for the Saudi-led coalition fighting in Yemen.

On that war, the kingdom has moderated its position, accepting a UN-brokered truce this year and stepping up negotiations with Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Mr Biden has praised these moves and says he will be looking to further advance efforts towards peace.

What do the Saudis want?

In fact, MBS, who blames Khashoggi’s killing on rogue elements of his security forces, has delivered on a number of US requests and wants to be rewarded with a reset in relations, starting with a stronger bilateral security agreement.

The Saudis also want clarity on Mr Biden’s intentions, said Jonathan Panikoff, a former national intelligence officer now with the Atlantic Council.

“It wasn’t as if the president came into office and fundamentally altered the relationship with Saudi Arabia. It’s just been in purgatory for the last 18 months of nobody knowing where it was going to go,” he said.

“The lack of clarity is worse in a number of minds… there’s then just a clear message: yes we’re going to be your partner or no, we’re not going to be your partner.”

The Saudis see the visit “as a reset and also a vindication in that this recognizes that the kingdom cannot be ignored,” adds Ali Shehabi, a writer and commentator with a history of advocating MBS reforms in Washington.

Is he doing what Trump did?

Mr Biden has sought to dispel the impression that despite his claim to champion democracy and human rights, his Middle East policies look little different from those of his predecessor.

“We reversed the blank cheque policy we inherited,” he wrote in a Washington Post column recently.

But he also made clear that the war in Europe has helped reshape his view of the region’s strategic importance, especially that of Saudi Arabia. The kingdom strengthened relations with Russia and China during Biden’s absence.

Crucially, it has resisted US pressure to take significant steps to isolate the Russian President Vladimir Putin, with whom the crown prince has good relations.

“We have to counter Russia’s aggression, put ourselves in the best possible position to outcompete China, and work for greater stability in a consequential region of the world,” Mr Biden wrote. “To do these things, we have to engage directly with countries that can impact those outcomes. Saudi Arabia is one of them.”

That’s a long-term trade-off unlikely to result in any meaningful accountability for Jamal Khashoggi’s death. The danger to Mr Biden is if the trip serves simply to underscore that.