John Boorman’s film about an outward-bound trip gone wrong was one of the most unnerving of the 1970s. Fifty years on, Adam Scovell talks to Boorman and explores its meaning.

Based on James Dickey’s best-selling novel, Deliverance (1972) marked a highpoint in the work of British director Sir John Boorman. Having made the successful jump to Hollywood several years before, Boorman directed some of the strongest films of the period. In particular, Point Blank (1967) and Hell in the Pacific (1968) confirmed him as a director of note in the 1960s. Boorman went on to have a highly successful career, his films littered with prizes, while he received a Bafta fellowship in 2004 and, earlier this year, a knighthood. Yet Deliverance, released in the US 50 years ago this weekend, is the work that stands out in his varied and accomplished catalogue of work, not simply for its qualities but as one of the most controversial and unnerving films of the 1970s.

It centres on four city boys on an outdoor weekend around the fictional Cahulawassee River (really Georgia’s Chattooga River) in the Appalachian mountains. Lewis (Burt Reynolds) is the group’s natural leader, determined to take the other three away from their more usual golf courses to face the forces of nature. The river and its surrounding area are about to be flooded for a dam. Ed (Jon Voight) looks up to Lewis’ machismo, while Bobby (Ned Beatty) and Drew (Ronny Cox) are perplexed and amused by the trip, as well as ignorant of the dangers of the landscape and condescending to the local mountain community. They drop off their cars and take to the water, in spite of warnings about the perilous rapids. What follows for the four men is a brutal weekend of survival, not simply facing off against the landscape, but also several locals, who are far from welcoming.

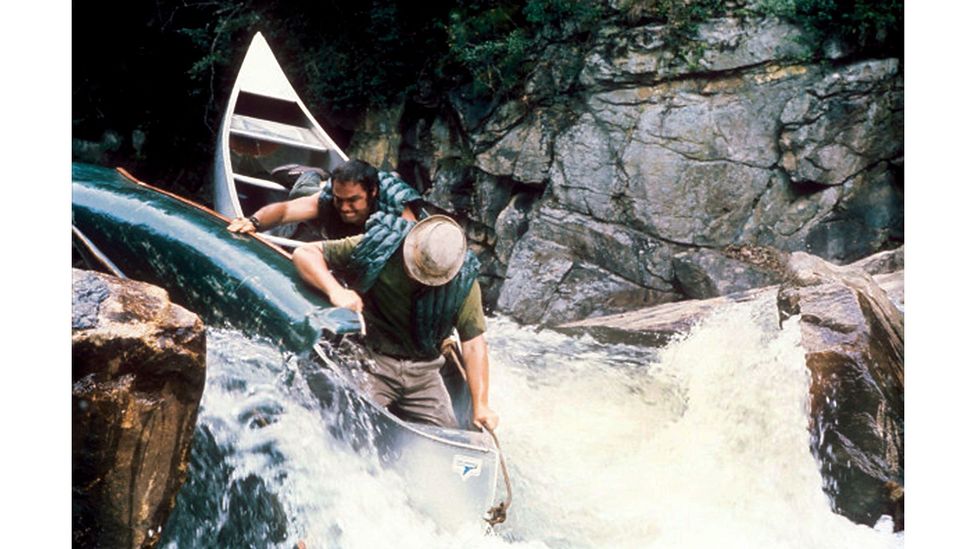

At heart, the film is a clash between four city-dwellers and the forces of nature (Credit: Alamy)

Deliverance shows Boorman’s skill as a director, achieving his usual visual flair but with a decidedly more disturbing subject matter. The film is remembered for two sequences especially: one of “duelling banjos” in which Drew and a local boy (Billy Redden) conjure up an impromptu duet between banjo and guitar, and an infamous scene where Bobby is sexually assaulted and ordered to “squeal like a pig”.

Fifty years on, Boorman tells BBC Culture that the film was a challenging one to make from the off, recalling how the studio Warner Bros was uncertain about its content. “It was a pleasurable location and a good cast,” he says, “but the studio was beating me over the head to reduce the budget. They really didn’t want to make the film in the end. They got cold feet about the rape in particular. Studios, when they don’t want to make film, reduce your budget hoping you’ll go away. They finally reduced it to $2m and I still made it with a profit in the end.”

Just like the characters of his film, Boorman exhibits a streak of defiant determination in the face of adversity, even today, aged 89, having retired from filmmaking after 2014’s Queen and Country. “It’s a tough world making movies,” he says with an undeniable fondness. “If you want to fight for your ideas and principles, it’s tough. But we did it.”

Deliverance stands as a powerful exploration of the harshness of the rural landscape, one with an ecological message that still resonates; that the destruction of the natural world has consequences for everyone. But the other aspect, one that has provoked a more divided response over the years, is its portrayal of “local” folk. In many ways, it defined a very particular branch of US cinema – one that became particularly popular in the 1970s, and expressed an abject fear of those who lived outside of cities.

People vs landscape

The link between place and people is incredibly important in Deliverance. In fact, it’s arguably the main driver of the division between the central urbanite quartet and the many country folk, or “mountain men”, who appear. Boorman explores his characters initially through their relationship to topography before delving deeper. The locals seem to be a part of the landscape while the vacationers are outsiders wanting to conquer it for their own personal ends; a common theme of what is often labelled the Southern Gothic. The genre first came to prominence in literature of the 20th Century, with authors such as William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams. Moving on to the big screen, filmmakers ran with its visual and atmospheric potential in films ranging from Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955) and J Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962) to Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971). Filmmakers made the most of the genre’s dark and Gothic portrayal of the Southern States; highlighting in particular an almost surreal grotesquery they saw as embedded in the Deep South.

It was really about men living in a city suddenly experiencing nature in all its terror. That was what people identified with – John Boorman

Dr Bernice Murphy, a researcher from Trinity College Dublin who specialises in the Southern Gothic, believes Deliverance to be a good example of what the genre does, especially with regards to people and place. “The Southern Gothic generally depicts the region as a place that has been left behind by the rest of the United States,” she tells BBC Culture, “and which is dangerously in thrall to the self-aggrandising myths of the Old South. Deliverance is a superb example of the Southern Gothic meets backwoods horror narrative: the Georgia wilderness is here depicted as a place set apart from the rest of the world.”

From the very beginning, the four vacationers are shown in contrast to the local people in virtually every conceivable way. Whereas the mountain folk have vehicles rusted to the point of collapse, the men travel in brand new cars, including an appropriately named Ford Country Squire. The car’s name alone hints at their naivety. Boorman highlights how the contrast between the men and the environment drove the film’s drama. “It was really about men living in a city suddenly experiencing nature in all its terror,” he says. “That was what people identified with.”

One of the key thrills of Deliverance is the high-octane rafting scenes, which John Boorman says contained “genuine danger” (Credit: Alamy)

If Deliverance has anything to say about the mountain folk, however, it is to not underestimate them. The drama comes precisely from the complacent attitude of the urban dwellers in ignoring the advice of wiser locals. One of the very first locals they encounter tells them to forget their trip, if only because of the river’s perils: the irony of the film, of course, is that the river hurts and eventually kills more effectively than the mountain men who attack them. When Drew is swept under by its currents, there’s an uncertainty as to whether he was shot before he fell and drowned, later shown to not be the case. Even the hardy Lewis is mangled by the river’s rocks rather than at the hands of a mountain man.

When it comes to the film’s most infamous moment, the brutal and seemingly random sexual assault, the two particular mountain men involved could be seen as manifestations of the land defending itself from those about to destroy it. There’s something almost fantastical about the horrifying scene, its randomness given no real narrative explanation. “Damming a river is almost like a sin against nature,” Boorman suggests when discussing the film’s ecological content. “To almost kill the flow of a river and turn it into still water is a horrible thing to do. But we do it.” It’s a sin that, within the film’s metaphorical framework, Bobby in particular pays the price for.

The men’s attackers could on one level be seen as a kind of manifestation of the anger felt by the landscape – Dr Bernice Murphy

Earlier in the film, Lewis uses the loaded word “rape” to describe what is happening to the land as diggers seen from afar prepare the damming project that will submerge the forest underwater and force local residents to move (“We’re gonna rape this whole goddamned landscape. We’re gonna rape it.”). Murphy notes that this acts as a horrible premonition of what is to come. “The attackers here could on one level be seen as a kind of manifestation of the anger felt by the landscape, their sexual assault of Bobby a brutal riposte to the ‘rape’ of the landscape mentioned in the film’s opening voice-over.”

Even many years on, that scene in particular still causes consternation for some local residents. For the film’s 40th anniversary in 2012, CNN journalist Rich Phillips revisited the Rabun County area in North-East Georgia used for filming to discuss Deliverance with various residents and some of its surviving cast. The response was still mixed. As the local county commissioner Stanley Darnell told Phillips, “We were portrayed as ignorant, backward, scary, deviant, redneck hillbillies… That stuck with us through all these years and in fact that was probably furthest from the truth. These people up here are a very caring, lovely people.”

In spite of this, the response at the time in the region was in fact generally positive, as Boorman remembers it. “The locals were very helpful. I kept in touch with several of them. They were really great and helped in all sorts of ways. The film was a great success and the locals were proud of having been involved in a film that was so successful. So there was a sense of loyalty there.”

Overall, it’s interesting that the two violent mountain men define the perception of the film, when other “locals” are much more sympathetically drawn. When the surviving three protagonists finally make it to the end of their trail, they find the people they encountered at the beginning of the film have been true to their word and driven their cars downriver for them. Indeed, the inhabitants of the area are helpful to them, even though it transpires that Ed may have killed an innocent local man, mistaking him for the surviving attacker from the earlier assault.

Its powerful legacy

Despite this, it was the two violent mountain men that left their mark on US cinema. The classic urban/rural divide that Deliverance foregrounded was one that would reoccur throughout US cinema in the years that followed, and in even more consciously terrifying forms, through many films in what constituted the “hillbilly horror” and “backwoods horror” sub-genres.

Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was one of the many films that followed Deliverance in creating terror out of the urban/rural divide (Credit: Alamy)

Even if the landscapes are decidedly different, it’s not too difficult to see the same underlying blueprint at play in movies like Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977). Both deal with outsiders entering the rural outback and finding communities embedded within it who don’t take kindly to being disturbed. Though the violence and characterisation is decidedly turned up to 11 – as is the wont in more out-and-out horrors like these – the continuity with Deliverance is undoubtedly there.

In hindsight, Deliverance and its successors can be seen as a response to the counter-culture trend that developed within the US during the 1960s for mostly middle-class people to leave the city and head into the country in order to drop out of the rat race. These 1970s films were satirising what they saw as the naïveté of such Back-to-the-Land-ism, which remained a popular tonic against the enveloping consumerism and violent globalism of the US, as 60s optimism gave way to 70s pessimism.

More specifically, the outward-bound-trip-gone-wrong also became a popular trope in North American thrillers and horrors that followed over the next decade, from William Grefé’s Whiskey Mountain (1977) to Peter Carter’s Rituals (1977) and Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort (1981), and many, many more. Most lack the overall quality of drama found in Boorman’s film, however, and certainly few matched its breathless tension and adrenaline-fuelled action. One thing Deliverance benefited from, in the dramatic stakes, was being shot in sequence, a rarity in Hollywood. “It was a great experience as it was probably the only time in my career that I shot the film in sequence,” says Boorman, “That was a great help for the actors, too, as they didn’t have to keep going back and forth.” The decision paid off, and Jon Voight ended up with a Golden Globe nomination for his performance, while Boorman was nominated for a best director Oscar.

I had a man ready to rescue the four lead actors all the time and they thankfully managed to stay alive – John Boorman

Interestingly, Deliverance had some positive real-world effects on the area where it was filmed. In spite of the portrayal of the landscape as brutal and the locals as unforgiving, tourism boomed in Georgia in the years following its release, and its action sequences kick-started the area’s craze for white-water rafting, now a multimillion-dollar industry, no doubt because aspiring daredevils were thrilled by the very real sense of jeopardy it conveyed. Indeed, Jon Voight’s stunt double Claude Terry went on to buy some of the actual rafting equipment used in the film and founded the oldest white-water rafting company in the local area, Southeastern Expeditions.

While all four leads had stunt doubles, the real actors did their fair share of dangerous filming on the water too. “I had four good guys, who were very brave,” Boorman recalls of filming the river sequences with his cast. “I had a man ready to rescue them all the time and they thankfully managed to stay alive. Ned Beatty said he could have overturned the canoe and gone under. He said, ‘How will John finish the film without me if I drown?’ And then his second thought was ‘That fucker will find a way to do it without me!'”

“There was a genuine danger in the rafting scenes,” he adds. “I wanted the men to experience the real situations. It was a joyous thing to go down the rapids and face that danger.” The scenes were genuine enough to effectively advertise the landscape to future thrill seekers.

This is the ultimate irony of Deliverance: for all that it made the Appalachians a source of horror, it genuinely brought a thriving tourism to the area of Rabun Country. In their 2012 story, CNN reported that a quarter of a million people visit the rapids each year just as Lewis and his friends did on that cursed weekend in 1972. Thankfully, however, the locals today are friendlier than a few of those met on that fateful trip downriver.