It’s become undeniable that black people – once missing from American whiskey bars and in the telling of whiskey’s story – have long played a role in creating the beloved spirit.

C

Che Ramos calls himself The Black Bourbon Guy. Ramos conducts tastings, teaches cocktail classes and consults with distillers and restaurateurs, all with the aim of making whiskey more accessible. As a black man who’d always enjoyed this spirit, he noticed that something was missing at American whiskey bars and in the telling of America’s whiskey story. Namely, black people.

Historical records from the 18th to the 20th Centuries in places like Kentucky and Tennessee don’t often credit black people for their contributions to the industry. Slaveholders, for instance, weren’t quick to share praise of the enslaved men who made up the majority of the whiskey workforce. And after slavery was abolished in 1865, segregationists in the Southern whiskey industry didn’t offer plaudits either. But it has become undeniable that black people had played a role in creating America’s favourite spirit.

None of this surprises Ramos. “When you study African American history, you find a lot of these stories in parallel industries,” he said. “It’s a ‘wow’ moment, but it’s also ‘Of course this happened. I’ve heard this story 100 times before.'”

The stories that Ramos tells at bars and homes across Durham, North Carolina, where he lives and conducts most of his classes and tastings, helps flip the script on whiskey’s history.

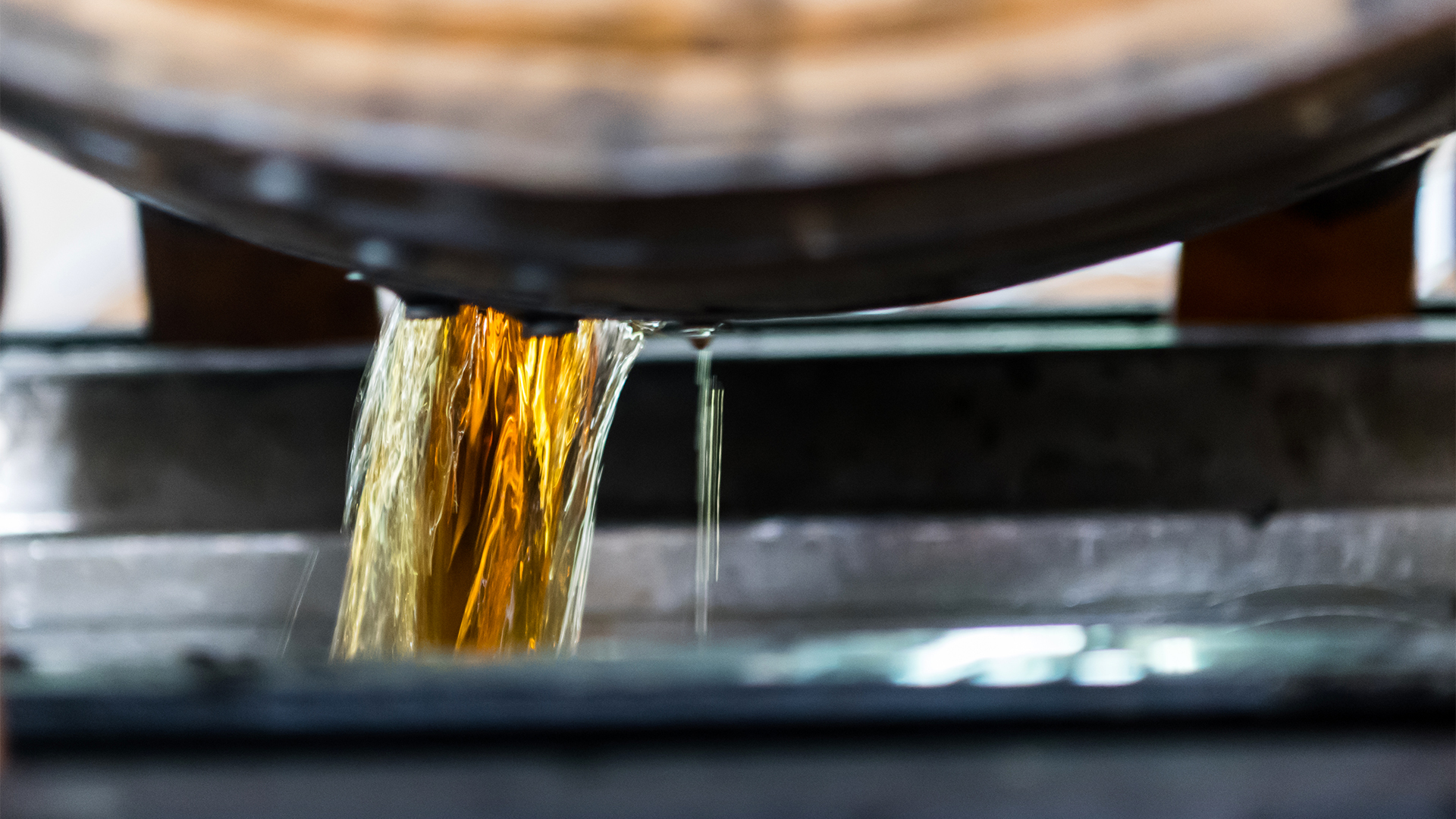

For instance, charred oak barrels, an indispensable component to whiskey making, might have come from the distilling practices of enslaved men who used the charcoal barrels to lessen the bite of their moonshine. President George Washington’s rye whiskey operation, one of the largest in the country at the time, was run mostly by slaves. And president Andrew Jackson once offered up a bounty to have his escaped distiller returned to him. The list of overlooked facts is long.

Che Ramos, The Black Bourbon Guy, aims to make whiskey more accessible (Credit: Forrest Mason)

Most famous, these days, is the story of Nathan “Nearest” Green, a former slave who taught Jack Daniel how to distil whiskey. The Jack Daniel‘s brand has started telling the story, and in 2017, Fawn Weaver, a black woman from California started the award-winning whiskey company that carries Green’s nickname – Uncle Nearest – bringing on board Green’s great-great granddaughter, Victoria Eady Butler to be the company’s master blender, making her the first-known black woman to ever hold that position at any whiskey company.

“The bourbon world is dominated by middle-aged white dudes with moustaches. Bourbon is not something we really associate with black people.”

“The bourbon world is dominated by middle-aged white dudes with moustaches,” Ramos said. “Bourbon is not something we really associate with black people.” Ramos jokes that he sometimes witnesses shock in a bartender’s face when he orders bourbon instead of cognac.

WHISKEY VS BOURBON

Bourbon is a type of whiskey made in the US that must comprise 51% corn (or more) and must be aged in new charred oak barrels.

One of the reasons cognac is associated with African Americans is because cognac producers in the 1950s made a concerted effort to target their advertising dollars to black publications like Ebony and Jet.

“They let the market know that they wanted their business,” said Shannon Healy, owner of Alley Twenty Six, a James Beard-nominated bar in Durham.

Each Wednesday, Healy hosts Whiskey Wednesday at his bar. They pour expensive, lesser-known whiskeys at break-even prices, aiming to educate their customers in a city where the black and white populations are both near 50%. Ramos has a residence at Alley Twenty Six one Wednesday each month where he educates customers on the whiskeys being poured that night.

“If we see someone doing something in the community whom we can support, we do it,” said Healy of Ramos. “What Che brings in is a more obvious opening line as how to communicate [the story of black contributions to American whiskey]. And it helps us to show to our market that bourbon is for black folks, too… even though many companies are not focusing on selling it to them.”

Of the few dozen black-owned distilleries in the United States, only a handful make whiskey.

Ray Walker, the owner and founder of Saint Cloud, a luxury bourbon company that contract distils in Kentucky and operates in California, wants whiskey to be for everyone, too.

Ray Walker founded luxury bourbon company Saint Cloud (Credit: Nick Brugioni)

Walker, whose mother is black and whose father is a white Kentuckian, however, is still trying to gain acceptance in the whiskey world. Typically, when he hands over his business card at a sales meeting or trade show – a card that reads CEO/owner – he receives an unsettling response.

“‘But who’s the big boss? But who’s the real owner?’,” Walker said, repeating lines from these interactions. “I’ve heard that from so many people.”

Doubt came from black people, too. After winning awards for his winemaking in France, Walker returned to the US to build Saint Cloud, driving an Uber simultaneously to raise capital for the company. He’d talk about Saint Cloud with black passengers, and the response was often, “They let a black man make bourbon?”

“Well, why not?” he would reply.

But there have also been unexpected surprises. “I thought it’d be very difficult to break into the Kentucky market,” Walker said, given his race and the traditionalism attached to bourbon. However, Kentucky was the first state to pick up his whiskey for distribution.

Black-owned Saint Cloud distils in Kentucky and operates in California (Credit: Karl Steuck)

Sometimes Walker receives messages on social media like, “Hey, I just bought your seven-year, brother”, which refers to Saint Cloud’s seven-year-aged bourbon. Curious to know his customer, he clicks on their Instagram page and can tell that their politics and values do not align with his.

“I love the fact that I look like me but have supporters like that.”

“I want my work to be appreciated first. I also want people to be cognizant that I’m different,” said Walker. “This is a chance that a lot of people who look like me didn’t get 50 or 60 years ago.”

“I want my work to be appreciated first. I also want people to be cognizant that I’m different.”

And for customers, this matters.

“If you look at the commercial face of whiskey, very rarely is it associated with a person of colour,” said Monique Culclough, a researcher at a large university in North Carolina, who hosted a birthday party whiskey tasting in a private residence for herself and nine friends. Ramos ran the tasting and helped present some new faces through new pours. “To know that behind the scenes there are black experts determining blends and styles meant a lot,” Culclough said.

Companies like Uncle Nearest are also aiming to change what the faces behind the scenes look like. Uncle Nearest’s CEO, Fawn Weaver, said that her company has allocated millions of dollars to a venture fund that helps support black-owned drinks companies “to provide access to capital”.

For most people who’ve never been to Louisville, Kentucky, but know it as the gateway to the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, the name of the city probably conjures up images of blue grass swaying and white distillers pouring straight from brown barrels.

But after the Breonna Taylor killing and the protests in the city in May 2020, Ramos noted, it was impossible for people watching the news to continue to assume that this is a land where only white men made whiskey, as Louisville is very much a black city. And for the 150 years after slavery ended, the industry has relied on black workers.

Kentucky’s whiskey industry relies on black workers (pictured: Buffalo Trace) (Credit: Jim West/Alamy)

Because of this, Ramos said, “there’s really no world where this industry explodes [around Louisville] without contributions from black people.”

On his first four-day tour along the Bourbon Trail, Ramos led a 50th birthday party group of 11 men – eight white, three minorities – to distilleries that do a better job of telling the story of African American involvement in whiskey. At Buffalo Trace, where a ginger ale is named for Freddie Johnson, a third-generation black employee and one of the company’s most sought-after tour guides, Ramos linked up his tour with Johnson, who shared his family’s story juxtaposed with the history of the distillery. At Old Forester, Ramos pointed out the displayed photograph of Elmer Lucille Allen, one of the first black chemists to work for a major distiller.

He skipped Belle Meade though, a distillery named for a plantation that had played a part in black suffering during the time of slavery, but does little today to confront that history, Ramos said. Rebel Bourbon was another pass, as the Confederate soldiers were infamously nicknamed “rebels”. (The company had recently changed their name from Rebel Yell, which was the battle cry used by the Confederates during the Civil War.)

Other distilleries have complicated stories, too. Bulleit, a distillery under multinational beverage company Diageo, is being sued by its former blender Eboni Major, whose whiskeys, like Blenders’ Select, were winning awards for the company. Major, who is black, alleges she was discriminated against by the company and her co-workers. Despite her success as a blender, she also claimed to be unfairly compensated, well below the average pay for her job title.

Fawn Weaver started award-winning whiskey company tUncle Nearest (Credit: Noah Lederman)

Along with curating thoughtful whiskey tours, Ramos also hosts tastings. A few months ago, he showed up to Roshaunda Breedan’s house with a box of some of his favourite bottles. Breedan, a university professor whose research interests are in black history and culture, had called Ramos to host a date-night rye whiskey tasting for her and her partner. During the blind tasting, Breedan also received an unexpected history lesson. It was the first time she’d heard about the influences black Americans have had on the whiskey industry.

Growing up, Breedan was not a drinker. “In the Christian tradition, you don’t drink alcohol or talk about it,” she said, alluding to her upbringing in the region commonly known as the Bible Belt. “In learning that we have cultural roots in whiskey… that changes the game.”

No longer could it be some forbidden spirit outlawed by the church of her youth; whiskeys, for Breedan, meant something else entirely after her tasting with the Black Bourbon Guy. She was “drinking for appreciation of the process and the cultural history”, Breedan said. “It definitely elevated our view of whiskey and the art form.”

These days, the professor invites friends over, pulls out bottles and the tasting sheets Ramos had left her, and passes along the history of how black Americans influenced the spirit.